Back in June when the first of the Black Lives Matter protests kicked off, a friend of mine reminded me of an incident that happened between high school and college. At the beginning of the year, I hadn’t intended to write about this one. In June, I committed myself to adding it to the queue.

As you might remember from “Homelessness”, that summer I was living on my own in an apartment, paying my own way with the suddenly full-time fast food job I had. I’d worked in that restaurant part-time for over two years.

My work history started when I was 16. A friend convinced me he could get me a job as a dishwasher at a local steakhouse where he was a busboy. It paid minimum wage. I wasn’t cut out for kitchen work. I lasted three weeks. I can still smell the miasma of wasted food piled in the thirty-gallon trash can set next to my station. I still feel the scalding plates burning my damp, uncalloused hands. I don’t know how another friend held down that same job for several years, but all due respect to anyone who can.

I quickly moved on to a local fast food restaurant where many of the students from my high school worked. That job was less strenuous and physically demanding. Somehow, I managed to score a position as a cashier rather than a cook, which was more than unusual. This was the early 80s. Girls worked up front, boys in back. I guess I was nonthreatening to the customers.

In general, I wasn’t bad at it. I showed up for my shift on time and worked when there was work to do. I could keep track of orders and could count out proper change. When things got slow, I looked for things to keep me busy, like cleaning windows in the dining room, which no one ever did. I was good enough that I eventually worked the drive-thru, which was reserved for only the best and fastest frontline crew.

The biggest drawbacks were that I earned a special “student” wage (below minimum) and that I came home smelling like grease. But otherwise, not the worst job I’ve ever had. In fact, other than unpredictable lunch and dinner rushes, and the occasional batch of buses that rolled through, it was a pretty easy gig, at least nights and weekends.

Easy enough in fact that some rainy nights we struggled for things to do even after our shift supervisors had sent home any extraneous crew. One of those nights, one when the owner’s son wasn’t working, after we’d done all the cleaning and pre-closing prep we could, an interesting conversation ensued with a supervisor. I’ll call her K.

I have no recollection of how it started. I just remember her saying to a number of us standing around, “Have you ever noticed we don’t have many black people working here? Ever wonder why that is?”

Sadly, I really hadn’t. There was one black guy from my neighborhood who usually worked frontline, just like me. Tall, about the same thin build. Non-offensive. But he was the only black person I worked with regularly.

One of my coworkers offered, because they don’t really eat here.

Which was and wasn’t true. Our cliental was predominately white but our restaurant was situated just across the tracks from the black community where two friends lived. We had black customers, just not as many as that proximity might indicate.

Another coworker piped up, because none of them apply?

That earned a dark glare from K. Oh they apply all right. I take their applications all the time.

Maybe they just aren’t qualified, someone said.

K sneered. Like what unique and essential skills do a bunch of high school students like us have? Scooping fries? Counting change? We were all teenagers. I think by this time K was out of high school but only just.

So, are you saying the owner is prejudiced, someone asked pointedly?

A kind of hush fell as we awaited her response. The owner was a city councilman and community business leader. Ours wasn’t a city where open racism was tolerated. This could be a pretty serious allegation. One that might cost a job.

K hesitated. I’m saying he keeps three sets of files for applications. Three very separate files.

Come on, I said. Really? Not sure if I believed or disbelieved.

In Florida, in the 70s and 80s it was hard not to encounter someone who was prejudiced. But my classmates and I had grown up in integrated schools. Sure, we had bussing and racial tensions, but this seemed like a throwback to a much different time from the 60s, which to a seventeen-year-old was ancient history.

At that point, K let the conversation drop. I could tell she was agitated that we hadn’t believed her, that we didn’t immediately see what she had seen. She also seemed cautious that she might have said too much. But later that night, just before we closed, she hauled me and another coworker into the office. Because she opened and closed the restaurant, she had keys. All the keys.

Close the door, she said. Which was a trick because this was a tiny office, barely big enough for a classic gunmetal grey office desk with drawers, a file cabinet and a chair. One of us did.

She unlocked and pulled open the built-in file drawer in the desk. She fished out three sets of file folders filled with applications and laid them on the desk, one from the front, middle and back of the drawer.

She opened the first set. These are the applications of people he would definitely hire. Take a look at them.

We did, not sure what we were supposed to see. One of us said that.

Look at the addresses, K said.

Then it stood out. Most of them from my neighborhood or the one right next to it.

She nodded, then opened the second file. Ok, these are people he might hire if he needs to but won’t if any of the people in the first file are still available.

We looked at them. Addresses from various neighborhoods all over the city.

Finally, she opened the third file. These are the people he will never hire.

My coworker looked at the addresses and didn’t recognize any of them.

I did, almost every one of them, and said so. As I mentioned in “The 2 O’clock News”, the Public Housing Authority had an unimaginative streak, naming streets and avenues for letters of the alphabet or numbers. Another handful of streets were named for flowers.

K asked us pointedly, what does that tell you?

I wasn’t sure what it told me. My mind tried to concoct scenarios that would justify what I was seeing, but I didn’t quite believe them. At the same time, I didn’t want to believe K either. I liked working here. I liked the people I worked with, although the owner was intimidating. I didn’t want anything to spoil that. And yet, seeing it right there in ink on paper made an impression.

K put the files away and relocked the desk drawer.

If you think he’s prejudiced, why do you work here, my coworker asked.

Because I need this job, she said.

Which confused me even more. Then why point it out, I wondered. K was clearly upset by what she’d noticed and needed to share it. I’m still not sure exactly why.

As far as I know, that conversation was never repeated again. I didn’t talk to anyone else about it. I just filed the information away and began looking at work interactions with a new set of eyes. At heart, I am an engineer, an applied scientist. I had suspicions but I wanted proof. So I watched and waited.

Fast forward an indeterminate number of months to the end of the summer I described in “Homelessness”. As I said, by then I was living in my own apartment, paying my own bills based on working days full-time, in the kitchen now, at this minimum wage job. Lunch was where the restaurant made its money. That and the recently added breakfast menu after a new fast food chain had bought our previous chain out. Forty hours a week of this work was both mind-numbing and much harder, especially working backline because the frontline supervisor, now the owner’s wife, didn’t cotton to males working her registers. At this point, I didn’t have much choice.

Toward the end of the summer my best friend, who lived in public housing, started complaining that his busboy job at the steakhouse I’d worked at before had started to go south. He’d asked to train as a waiter but the manager had refused. I think they’d also tried to restructure the way tips were shared by the wait staff with the busboys (which was supposed to be 10% of their tips but rarely was). Without those tips, the job didn’t make much economic sense as base wages were $2.01/hour. Like me, my friend needed the job, in his case to help support his household and pay for college.

One of the few advantages of working at this fast food joint was that a recommendation went a long way. If you were a marginally competent employee, it was trivial to get your friends hired.

So, I told him, if you need a job, I can get you a job where I work. We need people right now.

Really?

Sure, no problem. Just put me on the application as a reference. That’s the way it works.

He stopped in the restaurant the next evening and submitted an application to the night manager, who looked it over and took it noncommittally. We’ll let you know.

The owner did all his own interviews. Honestly, I don’t remember if he asked me about my recommendation. If he did, I know I reinforced it with as much positive information as I could.

Either way, my friend got a call for an interview. This should have been pro forma. The interview I had been through certainly was, as had every other one I’d heard of. It was basically a meet and greet followed by when can you start.

Or so I thought.

As it turned out, when my friend showed up, I had been just sent on break. Or I might have just finished my shift if I’d opened, as I often did at that point. Either way, I’d grabbed something to eat, so I was sitting out front at a small table about ten feet away from the booth where my friend and the owner talked. Not so close as to be able to hear every word, but close enough to witness what transpired.

As I ate, I kept stealing glances at their table. The owner’s back was to the counter so he couldn’t really see me. My friend could but he wasn’t looking. He was focused on the interview. Because I couldn’t hear, I was trying to read his body language to gauge how it was going.

At first, things seemed to be going well enough. Questions were asked and answered, the application consulted, more questions. My friend looked calm and poised, ready and capable. I started to relax. It would be really cool to work with him, and maybe have a schedule where we might get to do more together when we had time off.

Somewhere in there, my attention must have wandered. The next thing I knew, the owner shot up from his seat, yelling “Don’t tell me how to run my business!” And stormed off into the back. I looked at my friend. He looked just as stunned as I was. Like the few customers in the dining room were. Like all the counter help was. We were all like what the hell was that. None of us had ever witnessed anything like it. I certainly hadn’t in the two years I’d worked there.

I went over to the table where my friend was slowly gathering up his things. I asked him what happened?

He thought the interview had been going well. Then, the owner had asked him a pretty standard interview question. What do you bring to the business? That was a question I definitely don’t remember being asked, or hearing about anyone who was. But my friend was prepared and had done his homework, so it hadn’t thrown him. He was in the process of answering it when… Boom.

I’d seen his defeated expression on too many occasions, somewhere between crestfallen and resignation. At school, at businesses we frequented, by then at bars, where the black guy with the white guy was singled out for a little special attention, hassled for some minor thing. When the Rockledge cops would stop us and ask us what we were doing when we walked in my neighborhood at night. The time someone had rear-ended his car, driving us into the car in front of him, then hit and run. It took a nice white couple who had chased the car and returned with a partial license plate number to convince the officers that we’d been rammed into the car in front of us by the impact that gave us both whiplash and totaled his car. Or the time the deputy had pulled him over and told him in no uncertain terms to get “this piece of shit car off my road” when my friend was on his way to work. Or the time I’d gotten berated by my own father when I had brought a number of friends to his place to visit, at his encouragement, but failed to disclose that one of them was black. Or a year later, when my by then former girlfriend’s father told my friend that if he was coming around alone to see his daughter, he’d have to knock at the back door.

Imagine having that ore worse directed at you every day. No matter what you accomplish or who you become. No matter how much you prove yourself. (It is not a contest, Sadly, I know plenty of women and other people who could share similar or more horrific stories based on similar uncontrollable personal characteristics).

There was always context and subtext to these encounters, but I knew what was going on with all of them. If nothing else, because I listened to things that were said when my friend wasn’t around.

He didn’t have to say another word. I understood what had happened, too. I just hadn’t wanted to quite believe it because I liked this place and a lot of the people in it. But I did.

That late-night conversation with K in the office with the three sets of files came flooding back. As did every other troubling behavior I had noted since. The jokes, the looks, the postures and attitudes, and the tolerance of it in others. I’d been exposed to more of it on days than nights and weekends. As I said, you couldn’t grow up in Florida from the mid-60s to the early 80s and not encounter people who were prejudiced, even flat-out racist, no matter how hard they tried to disguise it. In that short time I’d never seen anything quite so crystal clear. I’d seen the teenaged equivalent of derelicts and degenerates hired on no more than an employee’s recommendation, without a twenty questions interview. White teenaged derelicts and degenerates.

One word sprang to mind that seemed to capture my boss’s interpretation of the situation. A word I’d heard many times before although never directed at me, because why would it be. But I wonder if it had been directed at K, or at least its implication, based on her assertiveness and her gender, not her race.

Uppity.

Ok, there’s a second word following that one in this case, but I’ll leave it to your experience or imagination to fill that one in.

I saw red. Deep, bloody, raging, aortic red.

I told my friend I would catch up with him later. I might have even seen him to the door. When I turned back to the employees’ entrance, I am sure my face was set. I knew what I had to do. I ignored the questioning looks from my coworkers behind the register. I marched straight back to the office when the owner was standing at his desk, annoyed at my interruption as I appeared in his doorway.

“Consider this my two-week notice,” was all I said.

He nodded perfunctorily like he was expecting it. And yet he was obviously still irritated as he shuffled applications on his desk.

I started to turn away without another word. Then he glared up at me, clearly feeling the need to say something.

“I’m not racist, you know,” he stated pointedly. An assertion, not a question.

No, I didn’t know. And I hadn’t brought it up. I guess I didn’t need to. It struck me then as now as an unintended confession. But I didn’t say anything. I just leveled an unbelieving gaze at him and left.

As I said earlier, I needed this job. I had bills to pay. But I didn’t need it bad enough to lay it on someone else’s back. Not like this.

I finished out the next two weeks, avoiding the owner where I could. The last morning that I was supposed to go in I just blew off. I was eighteen and didn’t figure I owed him. Petty revenge, but there it was. I still knew people on the night shift who would hand me my final check without question. Which they did.

The odd thing was, I didn’t feel good about quitting, I didn’t feel proud of it. I didn’t even feel like it was the right decision. For me, it hadn’t been a decision at all. It’s what I did because it’s what you do. Because it was right. Because there are times in the face of blatant wrongs like that, you have to stand up to be counted. And you sort out the consequences later.

It wasn’t a decision; it was a choice.

But I can’t say I wasn’t angry for having to do it. Not angry because my friend or the world put that expectation on me, because they clearly hadn’t. Angry at being put in the situation by other people’s unenlightened, benighted bigotry. Angry at a society that continued to allow it to exist. Angry that most people claimed we’d gotten past that and had moved on. Clearly not.

That anger stayed with me through my engineering career through the late 90s as I watched minorities and women treated with sometimes equal contempt, though by then more passive-aggressive and better disguised. But present nonetheless, sometimes in official corporate policy. Part of the reason I left engineering when I had the chance was that I couldn’t take the predominantly Neolithic attitudes in defense contracting.

But it wasn’t only there. In the 80s and the 90s I had micro-aggressions directed at me personally, both purposefully, mistakenly and inadvertently, at both work and school. In the early-2000s I ran across distinct anti-Semitism from an unexpected quarter, not disguised at all. Thankfully, it wasn’t as virulent as the first time I ran across it, twenty-five years earlier. It was just the first I’d heard it that direct in a long time. Which shouldn’t have surprised me much with the more subtle racism and sexism sometimes overlaid with it. Or in the 20-tweens when I had someone defend and justify using the n-word to me.

None of which is meant to say I am flawless. As I said, I grew up in the South, though at the time in a more moderate county (although perhaps not now). I made my mistakes and had to learn from them. There are distinct actions and attitudes that I am not proud of. I am certain I have contributed to other people’s pain. All I can say is that I’ve tried to learn from the experiences. Learn and listen.

Everything I’ve written so far might seem like ancient history. In writing these essays, I draw on my own experiences to make them relatable. Those I can speak to the accuracy of where as more contemporary events, I cannot always. But I can use my experiences to weigh them.

Let’s fast forward again to June this year when my friend reminded me of this incident. It wasn’t that I’d forgotten about it. I’ve told the story a handful of times before. I just hadn’t intended to write about it this year. What I think spurred me most was that my friend’s own brother hadn’t heard about this incident, though I might hazard a guess he knows about it now. The sad thing that says to me is that this incident might not have cracked my friend’s top ten so might not have been worth sharing, though it was worth his remembering nearly forty years later.

And in truth, he and his brother and his mother taught me more about their world than I could ever repay directly. They granted me a glimpse inside their lives, with patience and understanding. One small piece of a larger puzzle. An experience not everyone is fortunate enough to get. All I can do is pay the insight forward. Or try.

Here’s the thing. When people are as hurt and angry, as wounded as they’ve been during the recent demonstrations and protests, if you choose to refuse to consider their grievances, if you choose not to listen to why, if you choose to let their emotion overwhelm your empathy, you do so at your peril. That anger isn’t going to go away, not until the situation changes. And the situation absolutely must change. It’s what equality, equity and equanimity demand.

Now you can choose to believe things have changed since, say, the 60s or 70s, which some of you may not remember. Even since the 80s when this incident took place. They have, but likely not to the degree you would like to think. Don’t pat yourself on the back and say the work is done. It isn’t. Don’t rest on your laurels unless you never intend to open your eyes again.

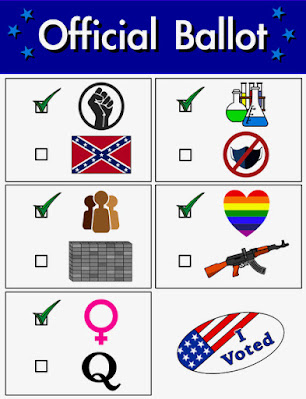

Especially in the past four years as naked racism, misogyny, antisemitism, homo- and xenophobia built upon a well laid and layered anti-diversity, anti-immigrant foundation has come back into vogue. In truth, that culture of hate never went away. It was just barely suppressed enough to where our society might show some modicum of disgrace when it reared its ugly head in public. We as a nation, as a united people, have chosen to no longer feel that sense of shame.

When a sitting President dog-whistles to white supremacists very publicly, not once but twice and then denies knowing who they are, when he calls out the regular military to clear protesters from a public park for a photo-op, when he and his Administration promote and support a vigilante who murdered protesters, when armed militias who are his direct supporters twice shut down a state legislature that was in session after his “Liberate” message, when the President threatens to have the leaders of the opposition party indicted, when he will not commit to a peaceful transition of power, when his allies and party leaders largely remain silent out of political expediency, we take one step closer to another Tulsa, another Rosewood, another Dozier School for Boys.

Preventing that comes down to the choices we each make in this life. Or in three days, the choices we will make. If not for yourself or your family and friends of color then for your wives and daughters, your children and grandchildren, for anyone else you know in situations of unequal, institutional power. Make your choice as if their lives depend on it. Because sadly, they just might.

© 2020 Edward P. Morgan III